The Federal Aviation Administration assigns every airport in the country a three-letter identification code. This abbreviation is useful shorthand for flight scheduling and also for simpler conversation. Usually these codes are tied to the name of the city, like Miami’s MIA or Dallas-Fort Worth’s DFW. Sometimes cities with multiple airports have an abbreviation which helps distinguish one local airport from another, like New York’s JFK or Washington-Dulles’ IAD.

One of the largest and busiest airports in the world carries the abbreviation ORD, which has little to do with either the name of its city or the name of the airport. Instead, ORD reflects Chicago-O’Hare International Airport’s origins as a small airfield in a crossroads known as Orchard Place.

The site which became O’Hare was a transportation hub even before air travel. The land was owned in the 1800s by the Wisconsin Central Railroad (later the Chicago and Northwestern), one of the many lines coming into the growing transportation center that was Chicago in those days. It was the railroad which named the piece of property Orchard Place.

Just as Chicago had become the rail center of North America, it would seek to become the aviation hub as well. As early as 1929, Alderman John Coughlin predicted in the Chicago Tribune that, “Chicago is destined to become the air center of United States, and adequate facilities should be provided without delay.”

That facility was the Chicago Municipal Airport on the southwest side. It opened in 1926, but the field which would come to be called Midway proved to be a less-than-ideal location. It was surrounded by development which made it difficult to expand for the growing popularity of air travel and the larger and heavier aircraft of future generations. The city was going to need another option.

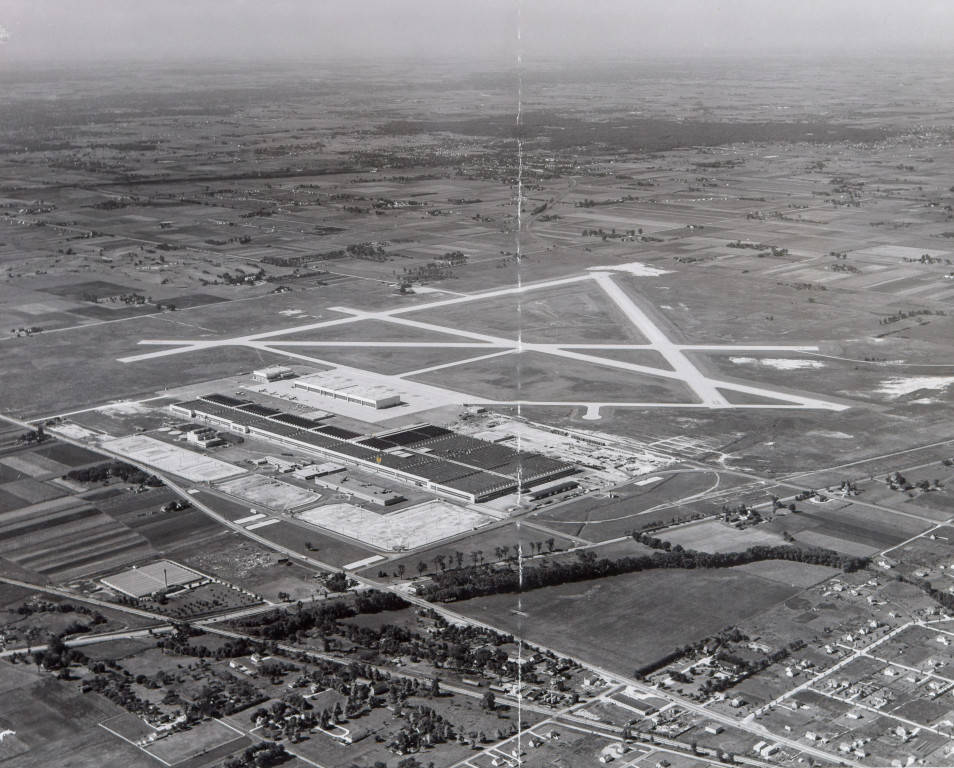

Northwest of Chicago meanwhile, out at Orchard Place, Douglas Aviation had built a factory at the start of World War II. The site had been aggressively promoted by E. Paul Querl who headed the Chicago Association of Commerce’s industrial and aviation development efforts.

The area northwest of the city was just what the War Department needed for building aircraft, Querl insisted, because it was close to so many natural resources and because its proximity to rail lines would prevent it from being inhibited by wartime restrictions on gasoline or tire rubber. The War Department looked at several sites in the Chicago area, including St. Charles, Aurora, Lansing and Joliet, but after a thorough investigation of every local factor they could think of, the Department chose Orchard Place.

Douglas Aviation saw the site’s potential as well, and not just for the immediate war effort. The company believed that Orchard Place would, “draw the best qualified factory personnel along with plenty of open space for future expansion into an international airport for Chicago.” In June 1942 the site was formally approved.

But not everyone was happy. In an echo of the concerns still heard eight decades later, local residents objected to the construction of a large factory and airfield so close to their homes. They raised questions about land use, noise and other considerations, but the War Department ultimately won out and construction soon began. The first runway was a 5500 foot airstrip.

The Orchard Place plant would get the contract for producing C-54 Skymaster cargo planes. Larger than the twin-engine C-47s then in use, the C-54s had both a longer range and a higher payload capacity for moving personnel and materiel for the war effort. In all, 655 of these aircraft would be manufactured at Orchard Place and they would move not only soldiers and equipment but also Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. After the war C-54s would be a crucial part of the Berlin Airlift and also fly in support of Americans fighting in Korea in the early 1950s. All this in spite of a large fire in July 1944 which wrecked the administration building and required help from ten fire departments to extinguish.

The Douglas plant was completed in 1943 and the first planes rolled off the line in July, a week before the formal dedication of the facility. As with other war plants around the nation, Orchard Place was staffed by large numbers of women. One of these workers, a riveter named Jennie Giangreco was given the honor of starting the engines on the first C-54 completed at the plant.

Fifty thousand people gathered for the celebration. They watched and cheered as Douglas test pilot Win Sargent took off and zoomed around the airfield’s vicinity for about a half hour. Speaking at the ceremony, Major General Harold George made a bold prediction for the future of Chicago and of aviation.

“Geography smiled generously on Chicago, for one need only to study the map of the world to see that it sits at the crossroads of many of the great air routes. How important will the position which this great city will take in the air transportation of the future depends upon the vision of its people, on their ability to see what lies just over the horizon,” the General said. “When that time arrives the airplane will become a great vehicle of peace. Great airlines will carry commerce to all parts of the world. A new era, that of world air transportation, will thrust itself into our peacetime economy”

But peacetime did not immediately bring prosperity to Orchard Place. With the end of the war in 1945, Douglas wrapped up its work at Orchard Place and closed down its operation. The airfield sat virtually unused, but its salvation would come from the continuing development to the south. Midway Airport was now completely hemmed in and city leaders knew they would need an alternate site for the ongoing growth of the city as an airline hub.

In 1946, the Chicago City Council began a survey of the land surrounding Orchard Place as a possible site for a new, larger commercial airport. Mayor Edward Kelly attended ceremonies in October of that year for the first cargo and mail planes which began using the field. Mayor Kelly put Ralph Burke, a sanitary district engineer in charge of the effort to turn the field into a major international airport. Kelly was able to work out a deal with the military to turn the property over to the city at no cost, provided that the government could continue to use one quarter of the property for its own purposes, such as mail delivery flights.

Two years of negotiations then began between Kelly, his successor as mayor Martin Kennelly, the airlines and an assortment of state and federal agencies. Agreement was finally reached in the fall of 1948.

Burke traveled the country inspecting other cities’ airports. He reviewed every element, from loading ramps to baggage handling practices. At a lunch with United Airlines executive William Patterson, Burke first floated the idea of a jetway so that passengers did not have to de-plane into the brutal elements of a Chicago winter.

Determined to avoid the problems that had limited Midway’s development. Burke purchased more land around Orchard Place. He made sure the airport would have the ability not only to expand but to adapt to the changing needs and preferences of air travelers. Chicago’s new airport would have plenty of room for comforts like restaurants and waiting areas, but also innovations like high-speed taxiways and a futuristic system for fueling aircraft. There would also be room for adding dozens of additional gates.

City leaders felt the airport needed a new name. They chose to honor a Navy Medal of Honor pilot with Illinois connections who had lost his life in World War II, naming the field after Edward “Butch” O’Hare.

As the new engineering and construction progressed, airlines began using the airport more and more, as did the U.S. Air Force and the Illinois Air National Guard. In 1952, larger commercial aircraft like the Convair 240 and the Douglas DC-6; successor to the DC-4 which was the civilian version of the C-54; started flying in and out of O’Hare.

The first regularly-scheduled commercial flights were inaugurated in 1955, and on October 29 of that year the city’s new mayor, Richard J. Daley led a celebration at the airport to mark the occasion. A tremendous air show had been planned for a crowd of 100,000 spectators, but rainy weather had moved in and kept most of them away.

As the first regular passenger flight, TWA flight 94, left O’Hare for Paris, Daley was not downcast in the least, eager to promote his city’s new gateway to the world and its bright future.

“I consider O’Hare’s beginning as a long and firm step into the jet airline age now upon us,” the mayor said. “We have the space for expansion for vast future developments that may now be entirely unguessed”